Matt Levine has a post on the limitations of Bitcoin as a way of making payments. I think he makes some factual errors. For example, he states that “neither the buyer nor the seller normally pays any transaction fees” when making Bitcoin payments, citing the Bitcoin wiki page on transaction fees. Now, I’m not an expert on Bitcoin, or anything else for that matter, but I believe that 0.0001 BTC (1 mBTC, or millibitcoin), is, in practice, the minimum transaction fee, and that it would be hard to get your transaction processed for free these days.

He also says that the transaction fees that are actually paid are “for, essentially, odd-lot transactions”. Here’s the comment I left about this, which hopefully clarifies things a little:

Bitcoin transaction fees are, by default, a function of transaction size (in kilobytes), not transaction value (in bitcoins). The default appears to be 0.0001 BTC per thousand bytes, and that’s also the minimum.

Transaction size is only vaguely related to transaction value, and depends on the number of inputs (how many different addresses you’re funding the transaction with) and outputs (how many different addresses you’re sending too). If you have an address with a large number of coins—say, 1,000 BTC—and you're sending them all to a single recipient, then the transaction will be relatively small, and as far as I understand, the network will process it at a cost of 0.00001%.

On the other hand, if you have received a lot of small amounts over time and you want to consolidate them in a single address, or if you have a complicated script (rule for when the coins can be released), you could end up with a big transaction of small value, and a large percentage fee.

For example, here’s a fairly large transaction in block 278,331. I have no idea what the purpose of the transaction was, but it could have been consolidating coins from a few dozen addresses into a single address. The total value was 100 BTC, or about $78,000. The size of the transaction was 4,482 bytes, and the transaction fee was 0.0005 BTC, or 0.0005%.

The fee will typically be proportionately higher for small value transactions. In the same block, we have this transaction that paid 0.00011 BTC in fees. The value appears to be 0.07419827 BTC, but some of that was change, and I believe the actual value transferred was only 0.01109714 BTC, or $8.68. Since the fee was $0.09, the percentage transaction fee was a whopping 1%.

Now, this whole discussion was trying to compare Bitcoin to the payments infrastructure for US Dollars. I am not a huge Bitcoin booster and don’t think it will revolutionize everything, but I am a big critic of the USD payments infrastructure. I am biased towards thinking that anything would be better than what we have right now.

There are several different kinds of payments an individual might want to make:

- Small point of sale and online store payments to merchants. Mostly handled by credit cards and cash.

- Small payments to merchants, to pay bills. In the United States of America, done by check, recurring credit card transactions and ACH debits.

- Small payments to other individuals in the same country. In the US, mostly done by check, or services such as PayPal.

- Small payments to other individuals in a different country.

In my opinion type 1 and 2 payments basically work fine in the United States. It’s absurd how many checks are still mailed around the country, but the US financial sector has lowered the cost of check payments to close to the cost of a stamp, especially now that many checks are only transported once—from sender to recipient—and the recipient will scan the check in an online banking app, if he or she is an individual, or convert it into an ACH debit, if the recipient is a business.

Some of these payments are instant, or at least can be verified instantly, even if they are settled a few days later. Very few of them are irrevocable: a merchant receiving a credit card or ACH payment can never be entirely sure that there won’t be a chargeback later, with very high fees added on. That’s horrible for small businesses, but it makes things very easy and secure for consumers, and larger businesses can handle the risk.

It’s the US individual-to-individual payments market that I curse at more frequently. Here’s how it works in a moderately civilized country:

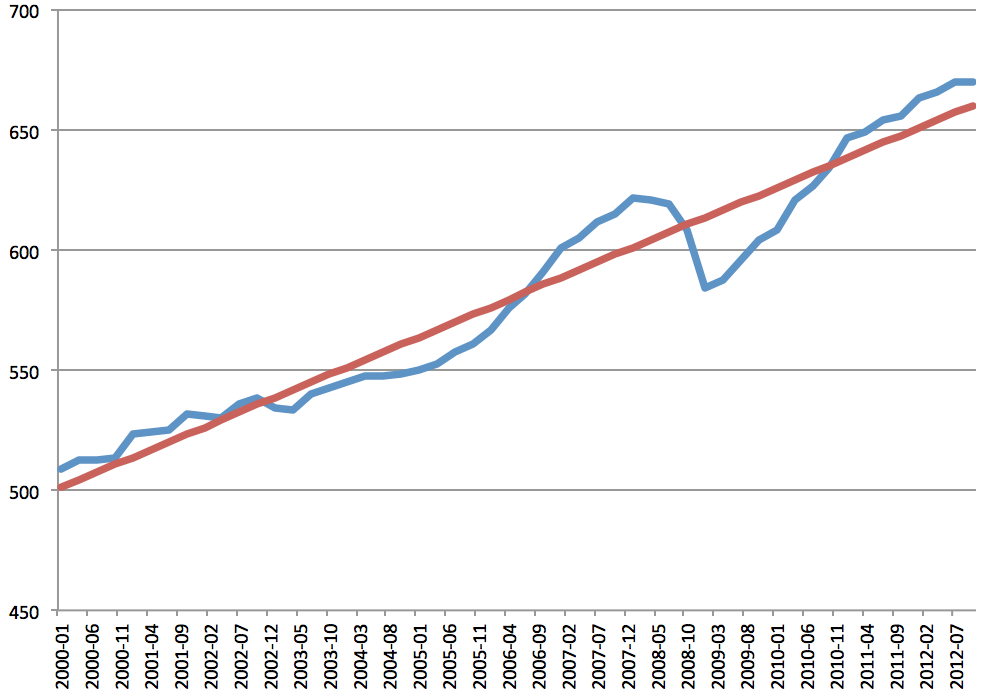

That’s my Danish online banking system. I put in the recipient’s routing number and account number, and amount, and click OK, and I can transfer up to 100,000 kroner (about $18,000) without interacting with a human or filling out a paper form. It’s free for me, and most people would pay no more than 1 kroner (about 18 cents) in transaction fees. Settlement takes one business day, with the money showing up before 6am, and can be withdrawn from an ATM or such immediately after settlement. Starting in 2014 there is a same day option.

(I can also make foreign payments this way, which either fall under SEPA rules and are very cheap, or are routed through SWIFT and are slightly less cheap. With foreign payments, the only additional piece of information I typically have to enter is the recipient’s name and address.)

Most European countries now settle this kind of payment several times a day, and a few settle it instantly. The payment is final and irrevocable, and you’d normally have to sue the recipient to get your money back. The fees are low enough that people would use it for very small payments, for example splitting a dinner check or small gambling debt.

Another benefit is that anyone can do this. The details vary from country to country (the UK is particularly bad in this area), but in practice, almost anyone can get a bank account, and so anyone can make payments to anyone else.

What are the options in the US?

- Travel to the recipient’s home and hand over cash.

- Mail a check.

- Use your bank’s “bill pay” service.

- Use an annoying service such as PayPal.

- Use a slightly less annoying service such as Square Cash or Popmoney.

The first two options are obviously slow, but they are effective. Cash payments are irrevocable.

There is no equivalent to putting in a recipient’s ABA routing number and account number and using the existing banking infrastructure to pay the recipient using the ACH system, which has very low transaction fees. For credit unions that use the ItsMe247 online banking system, you can fake it (but you’d probably violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and could end up in federal prison for 5 years) by doing the following: add the recipient as a “Person”, but put in your own email address. Then enter the recipient’s account information, pretending to be the recipient, and finally make the payment.

Of course giving your account number to a stranger can be dangerous in the US because of the way ACH is structured, where an account number is the only thing you need to steal someone’s money. (Don’t get me started on this.)

This kind of payment will typically take 2 or 3 business days. There is a system for same day ACH, but approximately zero financial institutions participate in it. And the payments are still not irrevocable.

What if you want to make an instant, irrevocable US dollar payment? You’d have to use Fedwire. The system transaction fee is less than a dollar, but most banks will charge you between $20 and $50 to do it. I don’t know of any US bank that allows individuals to do Fedwire transfers online, so you’d have to fill out a paper form and/or interact with a human being, who then has to input all your information into a computer. The payment is instant within Fedwire’s opening hours, but most US banks don’t have straight through processing for Fedwire on the receiving end, so you’d have to wait for a clerk at the receiving bank to manually credit the recipient’s account. If you’re lucky it could be done in an hour; most likely it will take a business day.

That leaves us with third party services such as PayPal. (Or really fifth party services, because the first four are the sender, the recipient, and their respective banks.) PayPal has a history of stealing people’s money without explanation. PayPal is incredibly annoying, at least in my personal experience: it can be very hard to get your account verified, it takes days to verify a bank account, and my US Social Security Number is rejected by most of these services because it has some kind of dirty foreigner flag attached to it. Many of these services will not let you mail documentation such as passports or social security cards to verify your identity: they will only accept the word of credit bureaus like Experian. It’s perfectly reasonable for a private company to reject me if I am too much hassle, but it doesn’t bode well for a payments system.

Square Cash is a lot better. I’ve been able to use it without any problems. Who knows what it will cost or what kind of hassle will be added when Square’s investors get tired of subsidizing it though.

I do think there’s a fundamental problem with these services. The recipient has to be signed up to actually get paid, so you end up having to maintain several different accounts simply to receive payments. Access is not guaranteed: these are private companies, so they can decide who they want to allow to become a customer, and a rejected customer can’t exactly appeal that decision. (You have the same problem with banks, but there are a lot of different banks and credit unions you could try, and in practice it’s very easy to get a bank account in the United States.) You are also subject to fairly arbitrary limits that you have little control or influence over.

If you want to make instant payments, most of these services, such as PayPal, only allow you to pay with USD balances that you’ve already settled with them, and it can take time for the recipient to get money out. This means that what you pay isn’t really a US Dollar in the traditional sense—cash or a checking account balance. Rather, you are paying PayPal balances.

There’s nothing wrong with innovation and competition in the payments market. Maybe you want to pay with your phone through text message. Maybe you want instant payments, and that’s not judged practical in an ACH like system because it would be harder to settle. Maybe you’d like to pay telepathically or telekinetically. There’s no way that the culturally conservative banking system is going to be first in those markets.

That doesn’t change the fact that the payments infrastructure for US Dollars—ACH in the United States of America—should provide a basic level of functionality for individuals.

Getting back to where we started, Bitcoin has obvious flaws that are well described by Matt Levine. But I would argue that US Dollars, while a good store of value and unit of account, are also terrible for making payments. Right now, for the typical American, it doesn’t do that: he or she cannot make payments to other typical Americans using the most common form of US Dollars, namely checking account balances.

Update: Shamir Karkal has a great reply with some corrections.